: Most upper respiratory infections are of viral etiology.

Epiglottitis and laryngotracheitis are exceptions with severe cases likely

caused by

type b. Bacterial pharyngitis

is often caused by Streptococcus pyogenes

: Organisms gain entry to the respiratory tract by

inhalation of droplets and invade the mucosa. Epithelial destruction may ensue,

along with redness, edema, hemorrhage and sometimes an exudate.

: Initial symptoms of a cold are runny,

stuffy nose and sneezing, usually without fever. Other upper respiratory

infections may have fever. Children with epiglottitis may have difficulty in

breathing, muffled speech, drooling and stridor. Children with serious

laryngotracheitis (croup) may also have tachypnea, stridor and cyanosis.

: Common colds can usually be recognized

clinically. Bacterial and viral cultures of throat swab specimens are used for

pharyngitis, epiglottitis and laryngotracheitis. Blood cultures are also

obtained in cases of epiglottitis.

: Viral infections are treated

symptomatically. Streptococcal pharyngitis and epiglottitis caused by

are treated with antibacterials.

type b vaccine is commercially available and is now a

basic component of childhood immunization program.

2. Lower Respiratory Infections: Bronchitis, Bronchiolitis and

Pneumonia

Etiology: Causative agents of lower respiratory infections are viral

or bacterial. Viruses cause most cases of bronchitis and bronchiolitis. In

community-acquired pneumonias, the most common bacterial agent is

Streptococcus pneumoniae. Atypical pneumonias are cause by

such agents as

Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia spp, Legionella,

Coxiella burnetti and viruses. Nosocomial pneumonias and pneumonias

in immunosuppressed patients have protean etiology with gram-negative organisms

and staphylococci as predominant organisms.

Pathogenesis: Organisms enter the distal airway by inhalation,

aspiration or by hematogenous seeding. The pathogen multiplies in or on the

epithelium, causing inflammation, increased mucus secretion, and impaired

mucociliary function; other lung functions may also be affected. In severe

bronchiolitis, inflammation and necrosis of the epithelium may block small

airways leading to airway obstruction.

Clinical Manifestations: Symptoms include cough, fever, chest pain,

tachypnea and sputum production. Patients with pneumonia may also exhibit

non-respiratory symptoms such as confusion, headache, myalgia, abdominal pain,

nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

Microbiologic Diagnosis: Sputum specimens are cultured for bacteria,

fungi and viruses. Culture of nasal washings is usually sufficient in infants

with bronchiolitis. Fluorescent staining technic can be used for legionellosis.

Blood cultures and/or serologic methods are used for viruses, rickettsiae, fungi

and many bacteria. Enzyme-linked immunoassay methods can be used for detections

of microbial antigens as well as antibodies. Detection of nucleotide fragments

specific for the microbial antigen in question by DNA probe or polymerase chain

reaction can offer a rapid diagnosis.

Prevention and Treatment: Symptomatic treatment is used for most

viral infections. Bacterial pneumonias are treated with antibacterials. A

polysaccharide vaccine against 23 serotypes of

Streptococcus

pneumoniae is recommended for individuals at high risk.

Upper Respiratory Infections

Infections of the respiratory tract are grouped according to their symptomatology and

anatomic involvement. Acute upper respiratory infections (URI) include the common

cold, pharyngitis, epiglottitis, and laryngotracheitis. These infections are usually benign, transitory

and self-limited, altho ugh epiglottitis and laryngotracheitis can be serious

diseases in children and young infants. Etiologic agents associated with URI include

viruses, bacteria, mycoplasma and fungi. Respiratory infections are more common in the fall and winter when

school starts and indoor crowding facilitates transmission.

Common Cold

Etiology

Common colds are the most prevalent entity of all respiratory infections and are

the leading cause of patient visits to the physician, as well as work and school

absenteeism. Most colds are caused by viruses. Rhinoviruses with more than 100

serotypes are the most common pathogens, causing at least 25% of colds in

adults. Coronaviruses may be responsible for more than 10% of cases.

Parainfluenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, adenoviruses and influenza

viruses have all been linked to the common cold syndrome. All of these organisms

show seasonal variations in incidence. The cause of 30% to 40% of cold syndromes

has not been determined.

Pathogenesis

The viruses appear to act through direct invasion of epithelial cells of the

respiratory mucosa, but

whether there is actual destruction and sloughing of these cells or loss of

ciliary activity depends on the specific organism involved. There is an increase

in both leukocyte infiltration and nasal secretions, including large amounts of

protein and immunoglobulin, suggesting that cytokines and immune mechanisms may

be responsible for some of the manifestations of the common cold.

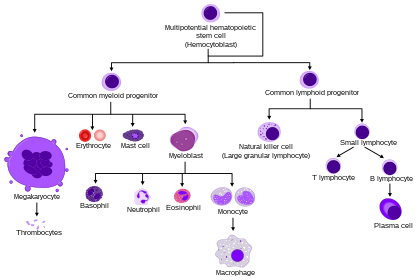

Pathogenesis of viral and bacterial mucosal respiratory

infections.

Pathogenesis of upper respiratory tract infections.

Clinical Manifestations

After an incubation period of 48–72 hours, classic symptoms of nasal

discharge and obstruction, sneezing, sore throat and cough occur in both adults

and children. Myalgia and headache may also be present. Fever is rare. The

duration of symptoms and of viral shedding varies with the pathogen and the age

of the patient. Complications are usually rare, but sinusitis and otitis media

may follow.

Microbiologic Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a common cold is usually based on the symptoms (lack of fever

combined with symptoms of localization to the nasopharynx). Unlike allergic

rhinitis, eosinophils are absent in nasal secretions. Although it is possible to

isolate the viruses for definitive diagnosis, that is rarely warranted.

Prevention and Treatment

Treatment of the uncomplicated common cold is generally symptomatic.

Decongestants, antipyretics, fluids and bed rest usually suffice. Restriction of

activities to avoid infecting others, along with good hand washing, are the best

measures to prevent spread of the disease. No vaccine is commercially available

for cold prophylaxis.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is an acute inflammatory condition of one or more of the paranasal

sinuses. Infection plays an important role in this affliction. Sinusitis often

results from infections of other sites of the respiratory tract since the

paranasal sinuses are contiguous to, and communicate with, the upper respiratory

tract.

Etiology

Acute sinusitis most often follows a common cold which is usually of viral

etiology. Vasomotor and allergic rhinitis may also be antecedent to the

development of sinusitis. Obstruction of the sinusal ostia due to deviation of

the nasal septum, presence of foreign bodies, polyps or tumors can predispose to

sinusitis. Infection of the maxillary sinuses may follow dental extractions or

an extension of infection from the roots of the upper teeth. The most common

bacterial agents responsible for acute sinusitis are Streptococcus

pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella

catarrhalis. Other organisms including Staphylococcus

aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, gram-negative organisms and

anaerobes have also been recovered. Chronic sinusitis is commonly a mixed

infection of aerobic and anaerobic organisms.

Pathogenesis

Infections caused by viruses or bacteria impair the ciliary activity of the

epithelial lining of the sinuses and increased mucous secretions. This leads to

obstruction of the paranasal sinusal ostia which impedes drainage. With

bacterial multiplication in the sinus cavities, the mucus is converted to

mucopurulent exudates. The pus further irritates the mucosal lining causing more

edema, epithelial destruction and ostial obstruction. When acute sinusitis is

not resolved and becomes chronic, mucosal thickening results and the development

of mucoceles and polyps may ensue.

Clinical Manifestations

The maxillary and ethmoid sinuses are most commonly involved in sinusitis. The

frontal sinuses are less often involved and the sphenoid sinuses are rarely

affected. Pain, sensation of pressure and tenderness over the affected sinus are

present. Malaise and low grade fever may also occur. Physical examination

usually is not remarkable with no more than an edematous and hyperemic nasal

mucosa.

In uncomplicated chronic sinusitis, a purulent nasal discharge is the most

constant finding. There may not be pain nor tenderness over the sinus areas.

Thickening of the sinus mucosa and a fluid level are usually seen in x-ray films

or magnetic resonance imaging.

Microbiologic Diagnosis

For acute sinusitis, the diagnosis is made from clinical findings. A bacterial

culture of the nasal discharge can be taken but is not very helpful as the

recovered organisms are generally contaminated by the resident flora from the

nasal passage. In chronic sinusitis, a careful dental examination, with sinus

x-rays may be required. An antral puncture to obtain sinusal specimens for

bacterial culture is needed to establish a specific microbiologic diagnosis.

Prevention and Treatment

Symptomatic treatment with analgesics and moist heat over the affected sinus pain

and a decongestant to promote sinus drainage may suffice. For antimicrobial

therapy, a beta-lactamase resistant antibiotic such as amoxicillin-clavulanate

or a cephalosporin may be used. For chronic sinusitis, when conservative

treatment does not lead to a cure, irrigation of the affected sinus may be

necessary. Culture from an antral puncture of the maxillary sinus can be

performed to identify the causative organism for selecting antimicrobial

therapy. Specific preventive procedures are not available. Proper care of

infectious and/or allergic rhinitis, surgical correction to relieve or avoid

obstruction of the sinusal ostia are important. Root abscesses of the upper

teeth should receive proper dental care to avoid secondary infection of the

maxillary sinuses.

Otitis

Infections of the ears are common events encountered in medical practice,

particularly in young children. Otitis externa is an infection involving the

external auditory canal while otitis media denotes inflammation of the middle

ear.

Etiology

For otitis externa, the skin flora such as Staphylococcus epidermidis,

Staphylococcus aureus, diphtheroids and occasionally an anaerobic

organism, Propionibacterium acnes are major etiologic agents.

In a moist and warm environment, a diffuse acute otitis externa (Swimmer's ear)

may be caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, along with other skin

flora. Malignant otitis externa is a severe necrotizing infection usually caused

by Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

For otitis media, the commonest causative bacteria are Streptococcus

pneumoniae, Hemophilus influenzae and beta-lactamase producing

Moraxella catarrhalis. Respiratory viruses may play a role

in otitis media but this remains uncertain. Mycoplasma

pneumoniae has been reported to cause hemorrhagic bullous

myringitis in an experimental study among nonimmune human volunteers inoculated

with M pneumoniae. However, in natural cases of M

pneumoniae infection, clinical bullous myringitis or otitis media

is uncommon.

Pathogenesis

The narrow and tortuous auditory canal is lined by a protective surface

epithelium. Factors that may disrupt the natural protective mechanisms, such as

high temperature and humidity, trauma, allergy, tissue maceration, removal of

cerumen and an alkaline pH environment, favor the development of otitis externa.

Prolonged immersion in a swimming pool coupled with frequent ear cleansing

increases the risk of otitis externa.

Acute otitis media commonly follows an upper respiratory infection extending from

the nasopharynx via the eustachian tube to the middle ear. Vigorous nose blowing

during a common cold, sudden changes of air pressure, and perforation of the

tympanic membrane also favor the development of otitis media. The presence of

purulent exudate in the middle ear may lead to a spread of infection to the

inner ear and mastoids or even meninges

Clinical Manifestations

Otitis externa

Furuncles of the external ear, similar to those in skin infection, can cause

severe pain and a sense of fullness in the ear canal. When the furuncle

drains, purulent otorrhea may be present. In generalized otitis externa,

itching, pain and tenderness of the ear lobe on traction are present. Loss

of hearing may be due to obstruction of the ear canal by swelling and the

presence of purulent debris.

Malignant otitis externa tends to occur in elderly diabetic patients. It is

characterized by severe persistent earache, foul smelling purulent discharge

and the presence of granulation tissue in the auditory canal. The infection

may spread and lead to osteomyelitis of the temporal bone or externally to

involve the pinna with osteochondritis.

Otitis media

Acute otitis media occurs most commonly in young children. The initial

complaint usually is persistent severe earache (crying in the infant)

accompanied by fever, and, and vomiting. Otologic examination reveals a

bulging, erythematous tympanic membrane with loss of light reflex and

landmarks. If perforation of the tympanic membrane occurs, serosanguinous or

purulent discharge may be present. In the event of an obstruction of the

eustachian tube, accumulation of a usually sterile effusion in the middle

ear results in serous otitis media. Chronic otitis media frequently presents

a permanent perforation of the tympanic membrane. A central perforation of

the pars tensa is more benign. On the other hand, an attic perforation of

the pars placcida and marginal perforation of the pars tensa are more

dangerous and often associated with a cholesteatoma.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of both otitis externa and otitis media can be made from history,

clinical symptomatology and physical examinations. Inspection of the tympanic

membrane is an indispensable skill for physicians and health care workers. All

discharge, ear wax and debris must be removed and to perform an adequate

otoscopy. In the majority of patients, routine cultures are not necessary, as a

number of good bacteriologic studies have shown consistently the same microbial

pathogens mentioned in the section of etiology. If the patient is

immunocompromised or is toxic and not responding to initial antimicrobial

therapy tympanocentesis (needle aspiration) to obtain middle ear effusion for

microbiologic culture is indicated.

Prevention and Treatment

Otitis externa

Topical therapy is usually sufficient and systemic antimicrobials are seldom

needed unless there are signs of spreading cellulitis and the patient

appears toxic. A combination of topical antibiotics such as neomycin

sulfate, polymyxin B sulfate and corticosteroids used as eardrops, is a

preferred therapy. In some cases, acidification of the ear canal by applying

a 2% solution of acetic acid topically may also be effective. If a furuncle

is present in the external canal, the physician should allow it to drain

spontaneously.

Otitis media

Amoxicillin is an effective and preferred antibiotic for treatment of acute

otitis media. Since beta-lactamase producing H influenzae

and M catarrhalis can be a problem in some communities,

amoxicillin-clavulanate is used by many physicians. Oral preparations of

trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, second and third generation cephalosporins,

tetracyclines and macrolides can also be used. When there is a large

effusion, tympanocentesis may hasten the resolution process by decreasing

the sterile effusion. Patients with chronic otitis media and frequent

recurrences of middle ear infections may be benefitted by chemoprophylaxis

with once daily oral amoxicillin or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole during the

winter and spring months. In those patients with persistent effusion of the

middle ear, surgical interventions with myringotomy, adenoidectomy and the

placement of tympanotomy tubes has been helpful.

Use of polyvalent pneumococcal vaccines has been evaluated for the prevention

of otitis media in children. However, children under two years of age do not

respond satisfactorily to polysaccharide antigens; further, no significant

reduction in the number of middle ear infections was demonstrable. Newer

vaccines composed of pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides conjugated to

proteins may increase the immunogenicity and are currently under clinical

investigation for efficacy and safety.

Pharyngitis

Etiology

Pharyngitis is an inflammation of the pharynx involving lymphoid tissues of the

posterior pharynx and lateral pharyngeal bands. The etiology can be bacterial,

viral and fungal infections as well as noninfectious etiologies such as smoking.

Most cases are due to viral infections and accompany a common cold or influenza.

Type A coxsackieviruses can cause a severe ulcerative pharyngitis in children

(herpangina), and adenovirus and herpes simplex virus, although less common,

also can cause severe pharyngitis. Pharyngitis is a common symptom of

Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus infections.

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus or Streptococcus pyogenes

is the most important bacterial agent associated with acute pharyngitis and

tonsillitis. Corynebacterium diphtheriae causes occasional

cases of acute pharyngitis, as do mixed anaerobic infections (Vincent's angina),

Corynebacterium haemolyticum, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and

Chlamydia trachomatis. Outbreaks of Chlamydia

pneumoniae (TWAR agent) causing pharyngitis or pneumonitis have

occurred in military recruits. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and

Mycoplasma hominis have been associated with acute

pharyngitis. Candida albicans, which causes oral candidiasis or

thrush, can involve the pharynx, leading to inflammation and pain.

Pathogenesis

As with common cold, viral pathogens in pharyngitis appear to invade the mucosal

cells of the nasopharynx and oral cavity, resulting in edema and hyperemia of

the mucous membranes and tonsils (). Bacteria attach to and, in the case of group A beta-hemolytic

streptococci, invade the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract. Many clinical

manifestations of infection appear to be due to the immune reaction to products

of the bacterial cell. In diphtheria, a potent bacterial exotoxin causes local

inflammation and cell necrosis.

Clinical Manifestations

Pharyngitis usually presents with a red, sore, or “scratchy”

throat. An inflammatory exudate or membranes may cover the tonsils and tonsillar

pillars. Vesicles or ulcers may also be seen on the pharyngeal walls. Depending

on the pathogen, fever and systemic manifestations such as malaise, myalgia, or

headache may be present. Anterior cervical lymphadenopathy is common in

bacterial pharyngitis and difficulty in swallowing may be present.

Microbiologic Diagnosis

The goal in the diagnosis of pharyngitis is to identify cases that are due to

group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, as well as the more unusual and potentially

serious infections. The various forms of pharyngitis cannot be distinguished on

clinical grounds. Routine throat cultures for bacteria are inoculated onto sheep

blood and chocolate agar plates. Thayer-Martin medium is used if N

gonorrhoeae is suspected. Viral cultures are not routinely obtained

for most cases of pharyngitis. Serologic studies may be used to confirm the

diagnosis of pharyngitis due to viral, mycoplasmal or chlamydial pathogens.

Rapid diagnostic tests with fluorescent antibody or latex agglutination to

identify group A streptococci from pharyngeal swabs are available. Gene probe

and polymerase chain reaction can be used to detect unusual organisms such as

M pneumoniae, chlamydia or viruses but these procedures are

not routine diagnostic methods.

Prevention and Treatment

Symptomatic treatment is recommended for viral pharyngitis. The exception is

herpes simplex virus infection, which can be treated with acyclovir if

clinically warranted or if diagnosed in immunocompromised patients. The specific

antibacterial agents will depend on the causative organism, but penicillin G is

the therapy of choice for streptococcal pharyngitis. Mycoplasma and chlamydial

infections respond to erythromycin, tetracyclines and the new macrolides.

Epiglottitis and Laryngotracheitis

Etiology

Inflammation of the upper airway is classified as epiglottitis or

laryngotracheitis (croup) on the basis of the location, clinical manifestations,

and pathogens of the infection. Haemophilus influenzae type b

is the most common cause of epiglottitis, particularly in children age 2 to 5

years. Epiglottitis is less common in adults. Some cases of epiglottitis in

adults may be of viral origin. Most cases of laryngotracheitis are due to

viruses. More serious bacterial infections have been associated with H

influenzae type b, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus and

C diphtheriae. Parainfluenza viruses are most common but

respiratory syncytial virus, adenoviruses, influenza viruses, enteroviruses and

Mycoplasma pneumoniae have been implicated.

Pathogenesis

A viral upper respiratory infection may precede infection with H

influenzae in episodes of epiglottitis. However, once H

influenzae type b infection starts, rapidly progressive erythema

and swelling of the epiglottis ensue, and bacteremia is usually present. Viral

infection of laryngotracheitis commonly begins in the nasopharynx and eventually

moves into the larynx and trachea. Inflammation and edema involve the

epithelium, mucosa and submucosa of the subglottis which can lead to airway

obstruction.

Clinical Manifestations

The syndrome of epiglottitis begins with the acute onset of fever, sore throat,

hoarseness, drooling, dysphagia and progresses within a few hours to severe

respiratory distress and prostration. The clinical course can be fulminant and

fatal. The pharynx may be inflamed, but the diagnostic finding is a

“cherry-red” epiglottis.

A history of preceding cold-like symptoms is typical of laryngotracheitis, with

rhinorrhea, fever, sore throat and a mild cough. Tachypnea, a deep barking cough

and inspiratory stridor eventually develop. Children with bacterial tracheitis

appear more ill than adults and are at greater risk of developing airway

obstruction.

Haemophilus influenzae type b is isolated from the blood or

epiglottis in the majority of patients with epiglottis; therefore a blood

culture should always be performed. Sputum cultures or cultures from pharyngeal

swabs may be used to isolate pathogens in patients with laryngotracheitis.

Serologic studies to detect a rise in antibody titers to various viruses are

helpful for retrospective diagnosis. Newer, rapid diagnostic techniques, using

immunofluorescent-antibody staining to detect virus in sputum, pharyngeal swabs,

or nasal washings, have been successfully used. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent

assay (ELISA), DNA probe and polymerase chain reaction procedures for detection

of viral antibody or antigens are now available for rapid diagnosis.

Prevention and Treatment

Epiglottitis is a medical emergency, especially in children. All children with

this diagnosis should be observed carefully and be intubated to maintain an open

airway as soon as the first sign of respiratory distress is detected.

Antibacterial therapy should be directed at H influenzae.

Patients with croup are usually successfully managed with close observation and

supportive care, such as fluid, humidified air, and racemic epinephrine. For

prevention, Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugated vaccine is

recommended for all pediatric patients, as is immunization against

diphtheria.

Lower Respiratory Infections

Infections of the lower respiratory tract include bronchitis, bronchiolitis and

pneumonia. These syndromes,

especially pneumonia, can be severe or fatal. Although viruses, mycoplasma,

rickettsiae and fungi can all cause lower respiratory tract infections, bacteria

are the dominant pathogens; accounting for a much higher percentage of lower

than of upper respiratory tract infections.

Bronchitis and Bronchiolitis

Etiology

Bronchitis and bronchiolitis involve inflammation of the bronchial tree.

Bronchitis is usually preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection or forms

part of a clinical syndrome in diseases such as influenza, rubeola, rubella,

pertussis, scarlet fever and typhoid fever. Chronic bronchitis with a persistent

cough and sputum production appears to be caused by a combination of

environmental factors, such as smoking, and bacterial infection with pathogens

such as H influenzae and S pneumoniae.

Bronchiolitis is a viral respiratory disease of infants and is caused primarily

by respiratory syncytial virus. Other viruses, including parainfluenza viruses,

influenza viruses and adenoviruses (as well as occasionally M

pneumoniae) are also known to cause bronchiolitis.

Pathogenesis

When the bronchial tree is infected, the mucosa becomes hyperemic and edematous

and produces copious bronchial secretions. The damage to the mucosa can range

from simple loss of mucociliary function to actual destruction of the

respiratory epithelium, depending on the organisms(s) involved. Patients with

chronic bronchitis have an increase in the number of mucus-producing cells in

their airways, as well as inflammation and loss of bronchial epithelium, Infants

with bronchiolitis initially have inflammation and sometimes necrosis of the

respiratory epithelium, with eventual sloughing. Bronchial and bronchiolar walls

are thickened. Exudate made up of necrotic material and respiratory secretions

and the narrowing of the bronchial lumen lead to airway obstruction. Areas of

air trapping and atelectasis develop and may eventually contribute to

respiratory failure.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection with a cough is the typical

initial presentation in acute bronchitis. Mucopurulent sputum may be present,

and moderate temperature elevations occur. Typical findings in chronic

bronchitis are an incessant cough and production of large amounts of sputum,

particularly in the morning. Development of respiratory infections can lead to

acute exacerbations of symptoms with possibly severe respiratory distress.

Coryza and cough usually precede the onset of bronchiolitis. Fever is common. A

deepening cough, increased respiratory rate, and restlessness follow.

Retractions of the chest wall, nasal flaring, and grunting are prominent

findings. Wheezing or an actual lack of breath sounds may be noted. Respiratory

failure and death may result.

Microbiologic Diagnosis

Bacteriologic examination and culture of purulent respiratory secretions should

always be performed for cases of acute bronchitis not associated with a common

cold. Patients with chronic bronchitis should have their sputum cultured for

bacteria initially and during exacerbations. Aspirations of nasopharyngeal

secretions or swabs are sufficient to obtain specimens for viral culture in

infants with bronchiolitis. Serologic tests demonstrating a rise in antibody

titer to specific viruses can also be performed. Rapid diagnostic tests for

antibody or viral antigens may be performed on nasopharyngeal secretions by

using fluorescent-antibody staining, ELISA or DNA probe procedures.

Prevention and Treatment

With only a few exceptions, viral infections are treated with supportive

measures. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in infants may be treated with

ribavirin. Amantadine and rimantadine are available for chemoprophylaxis or

treatment of influenza type A viruses. Selected groups of patients with chronic

bronchitis may receive benefit from use of corticosteroids, bronchodilators, or

prophylactic antibiotics.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammation of the lung parenchyma. Consolidation of the lung tissue may be

identified by physical examination and chest x-ray. From an anatomical point of

view, lobar pneumonia denotes an alveolar process involving an entire lobe of

the lung while bronchopneumonia describes an alveolar process occurring in a

distribution that is patchy without filling an entire lobe. Numerous factors,

including environmental contaminants and autoimmune diseases, as well as

infection, may cause pneumonia. The various infectious agents that cause

pneumonia are categorized in many ways for purposes of laboratory testing,

epidemiologic study and choice of therapy. Pneumonias occurring in usually

healthy persons not confined to an institution are classified as

community-acquired pneumonias. Infections arise while a patient is hospitalized

or living in an institution such as a nursing home are called hospital-acquired

or nosocomial pneumonias. Etiologic pathogens associated with community-acquired

and hospital-acquired pneumonias are somewhat different. However, many organisms

can cause both types of infections.

Pathogenesis of bacterial pneumonias.

Etiology

Bacterial pneumonias

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common agent of

community-acquired acute bacterial pneumonia. More than 80 serotypes, as

determined by capsular polysaccharides, are known, but 23 serotypes account

for over 90% of all pneumococcal pneumonias in the United States. Pneumonias

caused by other streptococci are uncommon. Streptococcus

pyogenes pneumonia is often associated with a hemorrhagic

pneumonitis and empyema. Community-acquired pneumonias caused by

Staphylococcus aureus are also uncommon and usually

occur after influenza or from staphylococcal bacteremia. Infections due to

Haemophilus influenzae (usually nontypable) and

Klebsiella pneumoniae are more common among patients

over 50 years old who have chronic obstructive lung disease or

alcoholism.

The most common agents of nosocomial pneumonias are aerobic gram-negative

bacilli that rarely cause pneumonia in healthy individuals.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter,

Proteus, and Klebsiella species are often

identified. Less common agents causing pneumonias include

Francisella tularensis, the agent of tularemia;

Yersinia pestis, the agent of plague; and

Neisseria meningitidis, which usually causes meningitis

but can be associated with pneumonia, especially among military recruits.

Xanthomonas pseudomallei causes melioidosis, a chronic

pneumonia in Southeast Asia.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis can cause pneumonia. Although the

incidence of tuberculosis is low in industrialized countries, M

tuberculosis infections still continue to be a significant

public health problem in the United States, particularly among immigrants

from developing countries, intravenous drug abusers, patients infected with

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and the institutionalized elderly.

Atypical Mycobacterium species can cause lung disease

indistinguishable from tuberculosis.

Aspiration pneumonias

Aspiration pneumonia from anaerobic organisms usually occurs in patients with

periodontal disease or depressed consciousness. The bacteria involved are

usually part the oral flora and cultures generally show a mixed bacterial

growth. Actinomyces, Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus, Veilonella,

Propionibacterium, Eubacterium, and

Fusobacterium spp are often isolated.

Atypical pneumonias

Atypical pneumonias are those that are not typical bacterial lobar

pneumonias. Mycoplasma pneumoniae produces pneumonia most

commonly in young people between 5 and 19 years of age. Outbreaks have been

reported among military recruits and college students.

Legionella species, including L pneumophila, can cause a

wide range of clinical manifestations. The 1976 outbreak in Philadelphia was

manifested as a typical serious pneumonia in affected individuals, with a

mortality of 17%.

These organisms can survive in water and cause pneumonia by inhalation from

aerosolized tap water, respiratory devices, air conditioners and showers.

They also have been reported to cause nosocomial pneumonias.

Chlamydia spp noted to cause pneumonitis are C

trachomatis, C psittaci and C pneumoniae.

Chlamydia trachomatis causes pneumonia in neonates and

young infants. C psittaci is a known cause for occupational

pneumonitis in bird handlers such as turkey farmers. Chlamydia

pneumoniae has been associated with outbreaks of pneumonia in

military recruits and on college campuses.

Coxiella burnetii the rickettsia responsible for Q fever, is

acquired by inhalation of aerosols from infected animal placentas and feces.

Pneumonitis is one of the major manifestations of this systemic

infection.

Viral pneumonias are rare in healthy civilian adults. An exception is the

viral pneumonia caused by influenza viruses, which can have a high mortality

in the elderly and in patients with underlying disease. A serious

complication following influenza virus infection is a secondary bacterial

pneumonia, particularly staphylococcal pneumonia. Respiratory syncytial

virus can cause serious pneumonia among infants as well as outbreaks among

institutionalized adults. Adenoviruses may also cause pneumonia, serotypes

1,2,3,7 and 7a have been associated with a severe, fatal pneumonia in

infants. Although varicella-zoster virus pneumonitis is rare in children, it

is not uncommon in individuals over 19 years old. Morality can be as high as

10% to 30%. Measles pneumonia may occur in adults.

Other pneumonias and immunosuppression

Cytomegalovirus is well known for causing congenital infections in neonates,

as well as the mononucleosis-like illness seen in adults. However, among its

manifestations in immunocompromised individuals is a severe and often fatal

pneumonitis. Herpes simplex virus also causes a pneumonia in this

population. Giant-cell pneumonia is a serious complication of measles and

has been found in children with immunodeficiency disorders or underlying

cancers who receive live attenuated measles vaccine.

Actinomyces and Nocardia spp can cause

pneumonitis, particularly in immunocompromised hosts.

Among the fungi, Cryptococcus neoformans and

Sporothrix schenckii are found worldwide, whereas

Blastomyces dermatitidis, Coccidioides immitis, Histoplasma

capsulatum and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis

have specific geographic distributions. All can cause pneumonias, which are

usually chronic and possible clinically inapparent in normal hosts, but are

manifested as more serious diseases in immunocompromised patients. Other

fungi, such as Aspergillus and Candida

spp, occasionally are responsible for pneumonias in severely ill or

immunosuppressed patients and neonates.

Pneumocystis carinii produces a life-threatening pneumonia

among patients immunosuppressed by acquired immune deficiency syndrome

(AIDS), hematologic cancers, or medical therapy. It is the most common cause

of pneumonia among patients with AIDS when the CD4 cell counts drop below

200/mm3.

Pathogenesis and Clinical Manifestations

Infectious agents gain access to the lower respiratory tract by the inhalation of

aerosolized material, by aspiration of upper airway flora, or by hematogenous

seeding. Pneumonia occurs when lung defense mechanisms are diminished or

overwhelmed. The major symptoms or pneumonia are cough, chest pain, fever,

shortness of breath and sputum production. Patients are tachycardic. Headache,

confusion, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea may be present,

depending on the age of the patient and the organisms involved.

Microbiologic Diagnosis

Etiologic diagnosis of pneumonia on clinical grounds alone is almost impossible.

Sputum should be examined for a predominant organism in any patient suspected to

have a bacterial pneumonia; blood and pleural fluid (if present) should be

cultured. A sputum specimen with fewer than 10 while cells per high-power field

under a microscope is considered to be contaminated with oral secretions and is

unsatisfactory for diagnosis. Acid-fast stains and cultures are used to identify

Mycobacterium and Nocardia spp. Most

fungal pneumonias are diagnosed on the basis of culture of sputum or lung

tissue. Viral infection may be diagnosed by demonstration of antigen in

secretions or cultures or by an antibody response. Serologic studies can be used

to identify viruses, M pneumoniae, C. burnetii, Chlamydia species,

Legionella, Francisella, and Yersinia. A rise in

serum cold agglutinins may be associated with M pneumoniae

infection, but the test is positive in only about 60% of patients with this

pathogen.

Rapid diagnostic tests, as described in previous sections, are available to

identify respiratory viruses: the fluorescent-antibody test is used for

Legionella. A sputum quellung test can specify S

pneumoniae by serotype. Enzyme-linked immunoassay, DNA probe and

polymerase chain reaction methods are available for many agents causing

respiratory infections.

Some organisms that may colonize the respiratory tract are considered to be

pathogens only when they are shown to be invading the parenchyma. Diagnosis of

pneumonia due to cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus,

Aspergillus spp. or Candida spp require

specimens obtained by transbronchial or open-lung biopsy. Pneumocystis

carinii can be found by silver stain of expectorated sputum.

However, if the sputum is negative, deeper specimens from the lower respiratory

tract obtained by bronchoscopy or by lung biopsy are needed for confirmatory

diagnosis.

Prevention and Treatment

Until the organism causing the infection is identified, decisions on therapy are

based upon clinical history, including history of exposure, age, underlying

disease and previous therapies, past pneumonias, geographic location, severity

of illness, clinical symptoms, and sputum examination. Once a diagnosis is made,

therapy is directed at the specific organism responsible.

The pneumococcal vaccine should be given to patients at high risk for developing

pneumococcal infections, including asplenic patients, the elderly and any

patients immunocompromised through disease or medical therapy. Yearly influenza

vaccinations should also be provided for these particular groups. An

enteric-coated vaccine prepared from certain serotypes of adenoviruses is

available, but is only used in military recruits. In AIDS patients,

trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, aerosolized pentamidine or other antimicrobials

can be given for prophylaxis of Pneumocystis carinii

infections.